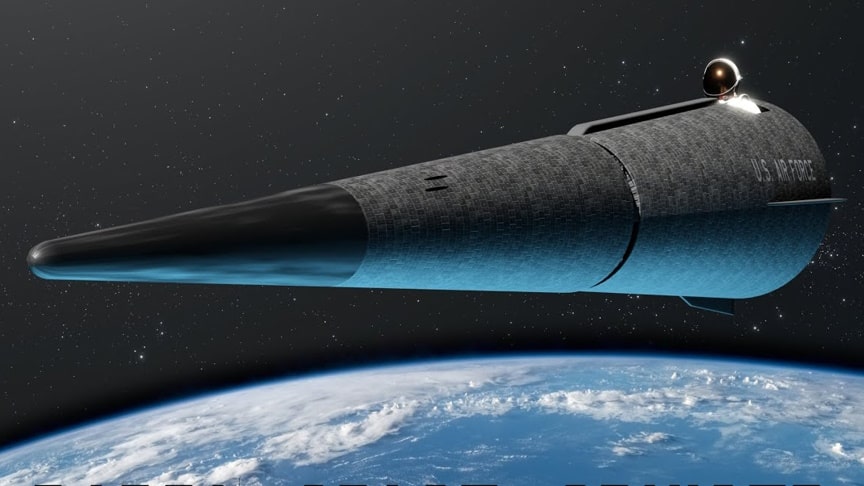

The fundamental concept behind the STAR program was to maximize efficiency while minimizing cost. To achieve this goal, the craft was designed to be as small and inexpensive as possible, with only one crew member onboard. The crew compartment itself was unpressurized and only large enough for a seated astronaut, who would be required to remain in their spacesuit throughout the duration of the mission.

source/image(PrtSc): Hazegrayart

Notably, the craft lacked key features such as hydraulics, an ejection seat, or even landing gear. Instead, it would utilize a parawing to glide back to Earth and touch down on land.

source/image(PrtSc): Hazegrayart

Despite its Spartan design, the STAR was intended to function as an orbital runabout, capable of carrying out a variety of missions. The craft was eight meters in length and only a meter and a half tall at its aft end, tapering down to a fine point at its nose.

Advertisement

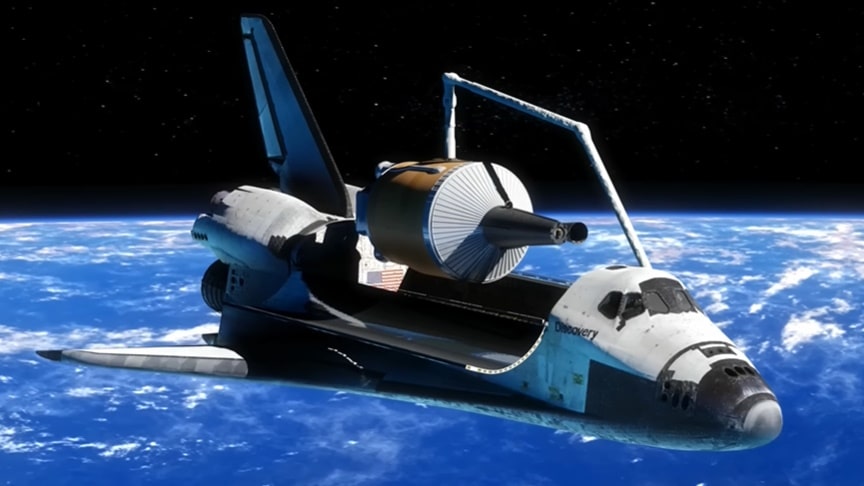

To optimize its transportability, the nose was designed to fold back at a hinge four meters down from the tip of the STAR, creating a compact package just four meters in length. In terms of deployment, the Shuttle was expected to lift the STAR into orbit, potentially even multiple at a time, and deploy them from its cargo bay.

Once in space, the STAR would set off on its designated missions, either returning to the Shuttle or making its own way back to Earth. If the STAR needed to reach higher altitudes beyond its on-board propellant capacity (which was estimated to be around 1650 kilometers), a truncated Centaur stage equipped with a single RD-10 engine – known as the Centaur-SP – could be attached to the STAR for increased thrust. This configuration would fit into the Shuttle’s cargo bay, allowing for transport to geosynchronous orbit and beyond.via: Hazegrayart